The first documented African men, women, and children were brought to the plot of land known as World’s End in 1747. This land was first occupied by the Algonquin-speaking Arrohattoc tribe and would become the headquarters of a series of plantations. Wilton’s enslaved community was a combination of first, second, and third-generation trafficked African people largely from Senegambia and the Bight of Biafra. By the 19th century, Wilton was home to the largest enslaved community in Henrico County. When Wilton plantation experienced financial collapse after four generations of Randolph ownership, it was its Black residents who paid the price. In 1783, 105 Black Virginians lived at Wilton. By 1833, gradual sales of enslaved Wilton residents to stave off plantation debt reduced their number to 27. By 1845, all of the people that had lived in bondage at Wilton had been sold. No known record exists of their fates. Little written record exists of their lives. The objects that they owned, purchased, cherished, resented, broke, played with, and discarded are all that remain to tell their stories. This is Wilton Uncovered.

Timeline of Virginian Slavery

-

The first Africans are forcibly brought to the North American English colonies from the Kingdom of Ndongo (modern Angola).

-

John Punch is sentenced to a lifetime of slavery as a punishment for fleeing his indenture.

-

Slave or free status determined by the “Condition of the mother.”

-

Baptism no longer exempts someone from enslavement.

-

The killing of enslaved people is legalized.

-

William Randolph I arrives in Virginia.

-

Randolph begins importing trafficked African people and European indentured servants to Virginia.

-

Interracial marriage is made illegal.

-

Enslaved men and women are legally property.

-

William Randolph I dies and leaves an unknown number of enslaved people as an inheritance to his son, William II.

-

Virginia outlaws the manumission, or freeing, of enslaved people.

-

William II actively imports an unknown number of trafficked Africans for profit.

-

William II dies and leaves an unknown number of enslaved people as an inheritance to his son, William III.

-

William III purchases ‘World’s End’ and renames it Wilton.

-

William III dies and leaves an unknown number of enslaved people as an inheritance to his son, Peyton.

-

Patrick Henry delivers his, “Give me liberty or give me death,” speech at St. John’s Church, 11 miles from Wilton.

-

Promised their freedom in exchange for fighting for England, 500 formerly enslaved men form the Ethiopian Regiment and wore uniforms featuring the words, “Liberty to Slaves.”

-

The manumission of enslaved people is made legal with certain restrictions.

-

Peyton dies, leaving 105 enslaved people as an inheritance to his son William IV.

-

Virginia ratifies the U.S. Constitution. The Commonwealth’s population is nearly 40% enslaved.

-

Gabriel, an enslaved man in central Virginia, plans but fails to carry out a slave rebellion in central Virginia.

-

William Randolph IV comes of age and serves as a justice in Henrico County, sitting in judgement of the accused conspirators in Gabriel’s Rebellion.

-

William IV dies and leaves 94 enslaved people as an inheritance to his son Robert.

-

Nat Turner leads a four day slave rebellion in Southampton County.

-

Robert Randolph dies. Twenty seven people remain enslaved at Wilton.

-

All people enslaved by the Randolphs at Wilton are sold to pay debts.

-

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolishes slavery except as punishment for a crime.

WAITING AT THE BOAT LANDING

The entrance road to Wilton connected four different worlds: the homes of five enslaved families, the opulent mansion of their enslavers, the surrounding network of farms and plantations, and the River that formed the economic and social network that connected them all. Close proximity to the James River would have given the people living here an intimate knowledge of and relationship with its waters. The river provided both food and the opportunity to engage in the broader local economy by purchasing and bartering from boats docked at the landing.

Here, Dorcas and a companion await an approaching boat. Depending on the identity of its occupants, this could be a chance to purchase wares, to catch up with friends or family, or to receive visitors to the main house that required Dorcas to navigate white Virginian expectations.

Chatelaine

English

Copper, gold, zinc

Threaded brass lid with gilding resembling an acorn cap. Chatelaines were typically worn by women and carried various items from perfume to keys. This vignette imagines this chatelaine as the possession of Dorcas, the enslaved housekeeper.

Parasol Rib

English

Copper, lead, zinc

Parasol umbrellas were popular accessories both in Africa and the mass dispersion of African peoples during the Transatlantic Slave Trade, also known as the African Diaspora. Unlike their more durable cousins, umbrellas, parasols provided shade from the sun. While parasols could be an important status symbol to free Black women, this example may have been used to shade white guests or members of the slaveholding household.

Virginian plantation complexes are often perceived as patriarchal, male-controlled spaces. At Wilton and beyond, however, the plantation landscape was normally divided by gender. Slaveholding women controlled the functions and decision-making of the domestic space and food production, and the lives of the Black men and women who worked in these spheres. At Wilton, this role was filled alternately by the wife or widow of a Randolph man, who on occasion expanded her role to the management of both household and crop production.

An enslaved woman typically filled the role of housekeeper and at times took on some of the domestic responsibilities of the slaveholding mistress. Unlike the people residing in the Landing Quarters, the housekeeper and others bound to the household would have little access to privacy or opportunities to generate personal income. Personal servants such as maids and valets, along with Wilton’s housekeeper, may have slept in a structure close by or on pallets within the home.

Click on each artifact for more information!

Dorcas

We know little about Dorcas and her life. We do know that by 1745, she was uprooted from the enslaved community that resided at Berkeley in Charles City County to the first marital home of the Randolph’s, Fighting Creek Plantation in Powhatan County. When Wilton was built in Henrico, she likely accompanied Anne Randolph as a personal lady’s maid. Dorcas may have experienced an elevated level of trust and access from the Randolphs, within the strict boundaries of her legal status. In 1784 the name Dorcas appears once more on a list of people enslaved at Wilton. If this is the same woman, she would have been at least in her 40s and would have outlived two male heirs of Wilton.

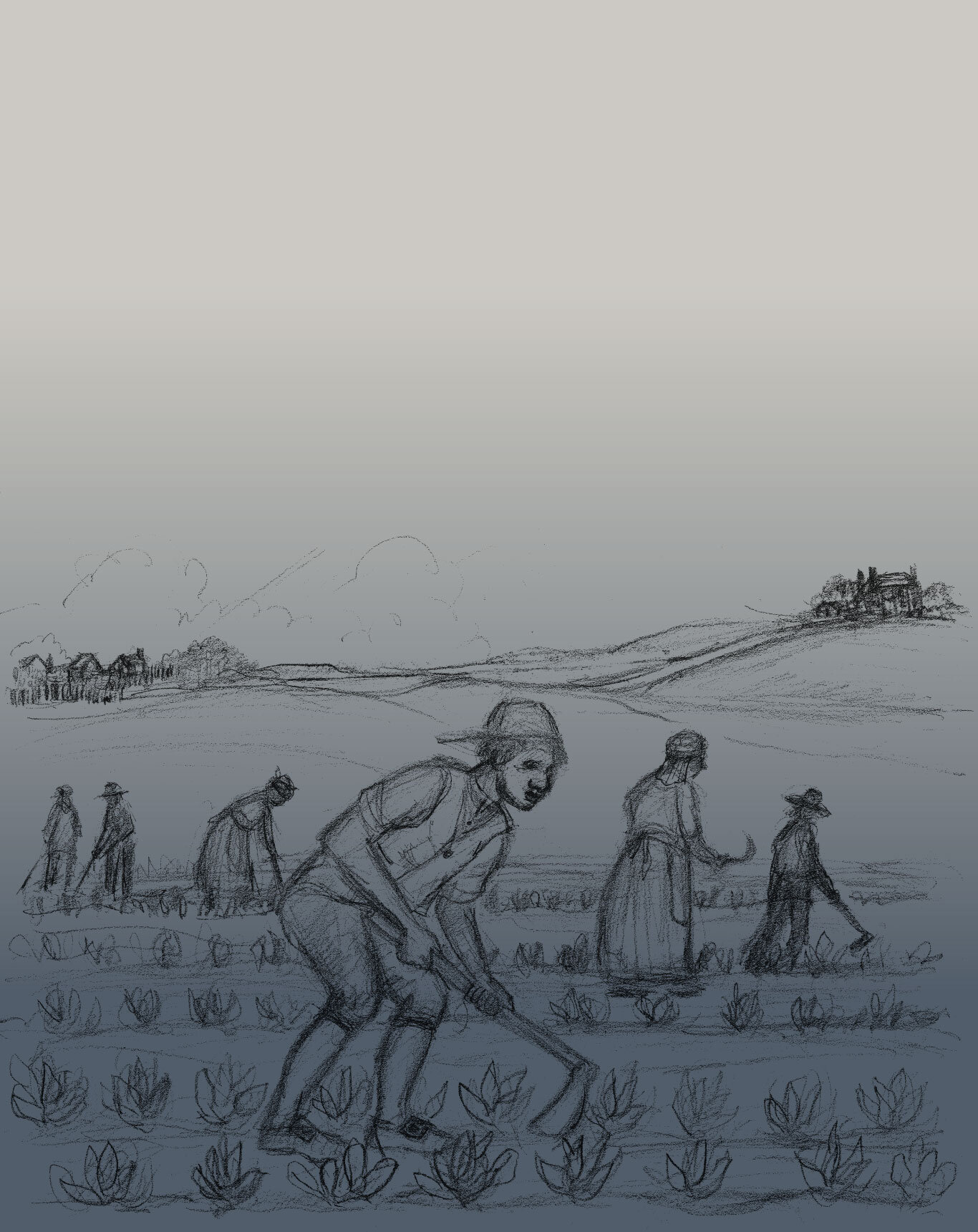

WORKING IN THE FIELDS

Just beyond the Landing Quarters stretched tobacco and wheat fields. Trafficked African men and women brought with them centuries of agricultural expertise: knowledge that was exploited in addition to their labor. Raising tobacco was a labor-intensive process that required year-round attention. In the 1760s Wilton was producing more than 100 hogshead barrels of tobacco a year. Shortly after the peak of their production, the collapse of tobacco prices drove the plantation deeper into debt.

Financial and archaeological records following this period suggest a gradual transition at Wilton from tobacco to wheat as a primary cash crop. For the men and women held in bondage at Wilton, this agricultural shift meant uncertainty. With less of their attention needed for crops, outcomes for Wilton’s residents could include hiring out to other plantations or to the urban city center of Richmond, changing responsibilities, or, worse, being sold away from loved ones.

Sickle

Virginian

Iron alloy

The shift from tobacco to wheat as a primary crop in Virginia was a gradual process over several decades. By the 1790s, large scale tobacco production had all but ceased in Tidewater Virginia. Wheat required little attention from sowing time to harvest time with far less preparation than tobacco. Fields were hoed or plowed, and then formed into ridges and furrows about four to seven feet apart. Wheat seeds were then often hand-sewn on the ridges. The spacing of the wheat meant that Virginian plots normally produced one half to one bushel of wheat per acre. Harvesting wheat with a sickle, like at Wilton, was called, “reaping,” and took approximately fifteen days.

A maker’s mark was found when this sickle was X-rayed during conservation, possibly representing a combined “I” and “E” or a combined “J” and “E.” This mark is so far unidentified. Its lack of a known match in recorded English maker’s marks suggest that it may have been locally made.

Tobacco farming was a labor intensive process that required nearly year round attention. Seeds were planted in warm beds of mounded earth early in the year and seedlings transplanted to the fields by early spring. Tobacco plants needed constant attention in the form of pruning and pest maintenance until the fall, when the leaves were stripped and cured in airy barns. Packed into barrels called hogsheads and shipped in early spring, the finished tobacco product was sold just as a new crop was moving into the fields. Overreliance on tobacco throughout fluctuating prices and seasons of poor crop performance lead to enormous debts among the planter class; debts that some enslavers, like those at Wilton, chose to pay at the expense of the lives of those they enslaved.

Life at Wilton was never secure for those living within the system of slavery. Financial records from the plantation are scarce, but an 1815–1821 account book can give us clues about how the Randolphs utilized sale as a threat and as a punishment. In December of 1820, a man named Nick was “sold for bad conduct.”

His fate is unknown, as are those of Dorcas and Ian, whose jail expenses were paid in 1818 and 1820, respectively. The Wilton Randolphs paid Richmond jailers to hold enslaved people they intended to sell, a thriving industry in Richmond’s Shockhoe Bottom district. While Lumpkins jail was one of the most notorious, it was just one of a larger network of jailers, traders, and speculators operating out of the state’s capitol.

Richmond, Virginia was one of the largest slave-trading centers in the United States. Exactly how many people were trafficked through Shockhoe is unknown, but at least 300,000 people were transported within one thirty-year period. By the 1830s, Virginia’s largest export was human property.

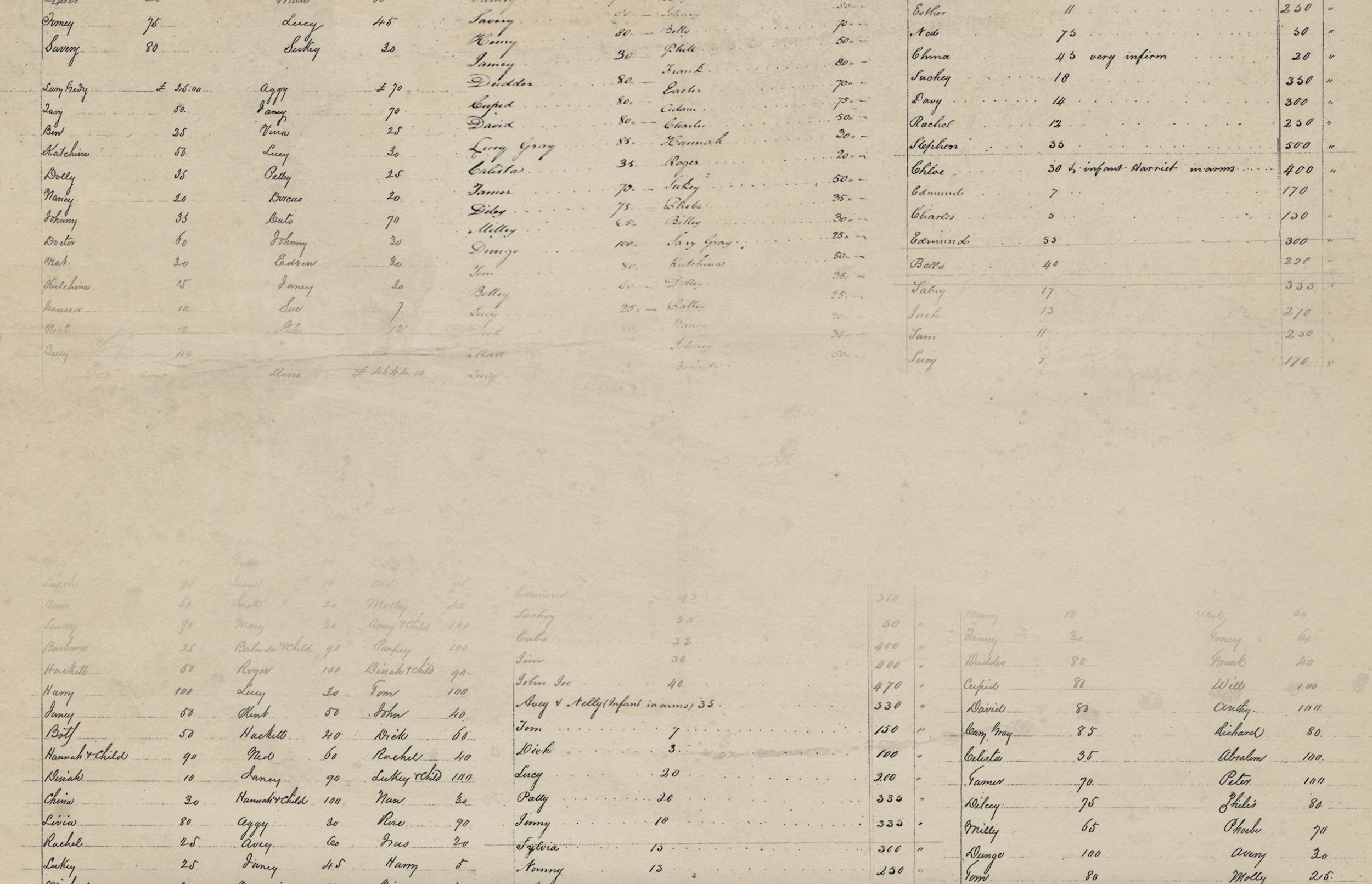

Lumpkin’s Slave Jail Ledger, 1835, 1848-1850

Courtesy of The Valentine Museum

Lumpkin’s Jail: A history of the Richmond Theological Seminary, with reminiscences of thirty years’ work among the colored people of the South, 1895.

Special Collections, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va.

SMALL TALK AND A BRIEF VISIT

Here we join a brief visit in the central shared yard of the Landing dwellings. Warwick stops by on horseback for some conversation, or perhaps to observe this game of marbles. Several generations of children had been raised here at the Landing by this scene from the late 1700s. The Landing Quarters began as a barracks-style building that probably housed 12–15 unrelated adults and children. By the late 18th century, the Landing community consisted of five buildings that probably housed individual families, a boundary fence, a central yard, and a nearby burial ground. The open yard at the Landing Quarters served as an important shared living space in times of mourning, in times of celebration and rest. This group of diverse individuals formed families and forged kinship, but always under the threat of change from their enslavers and while under the eye of a nearby overseer.

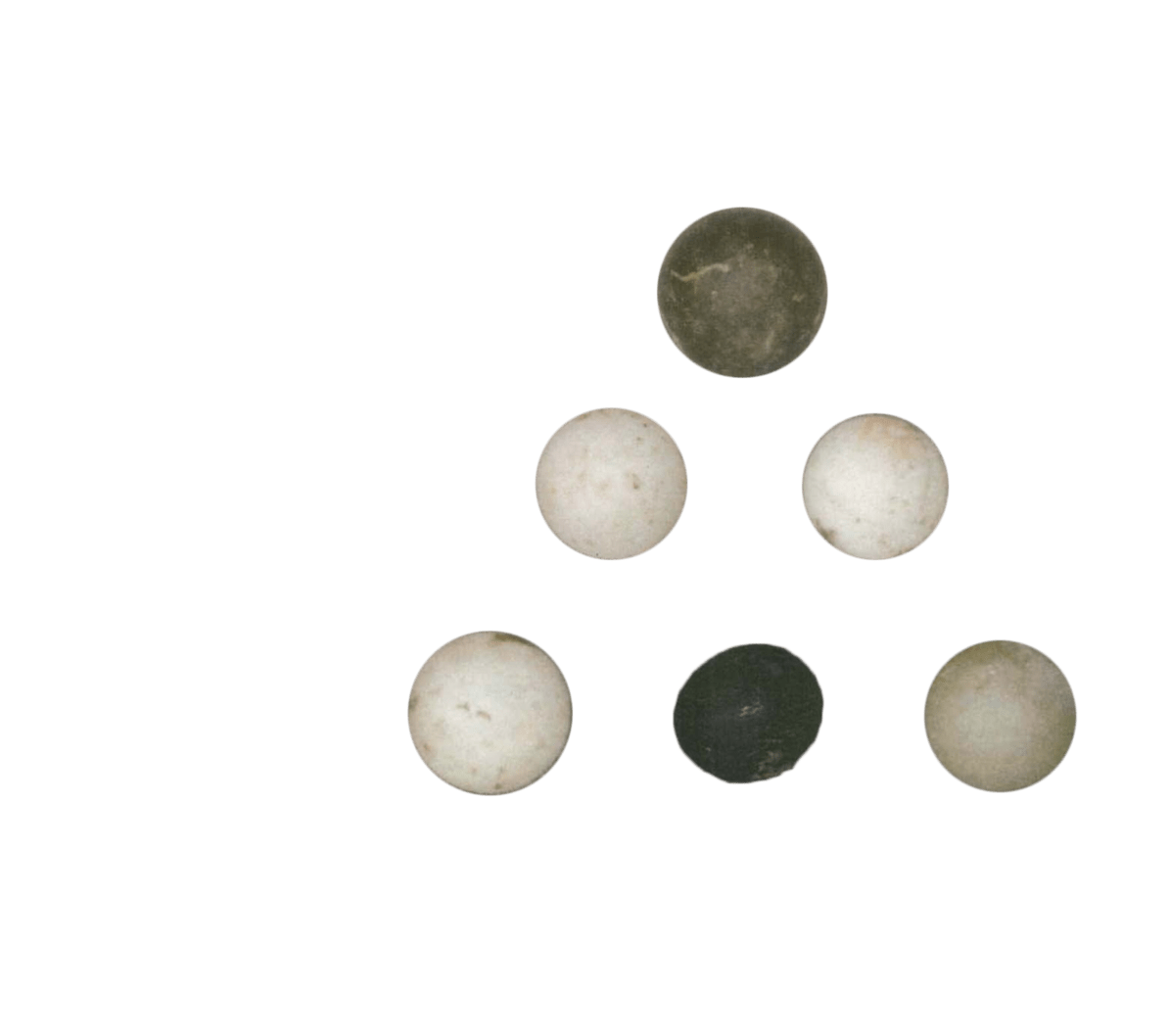

Marbles

Virginian, European

Stone, Ceramic

These marbles, made of both stone and ceramic, give us a rare glimpse into Black childhood at Wilton. Many children born into slavery had no playthings other than marbles, or what they could create at home. Marbles recovered from enslaved contexts in Virginia range from stone to porcelain to glass to clay. While clay marbles could be made at Wilton, many commercially produced marbles were imported from Germany. Playfulness may have blurred the lines between the Black children and white children of Wilton during these games, but time would soon harden the social divisions and inherent legal inequalities between them.

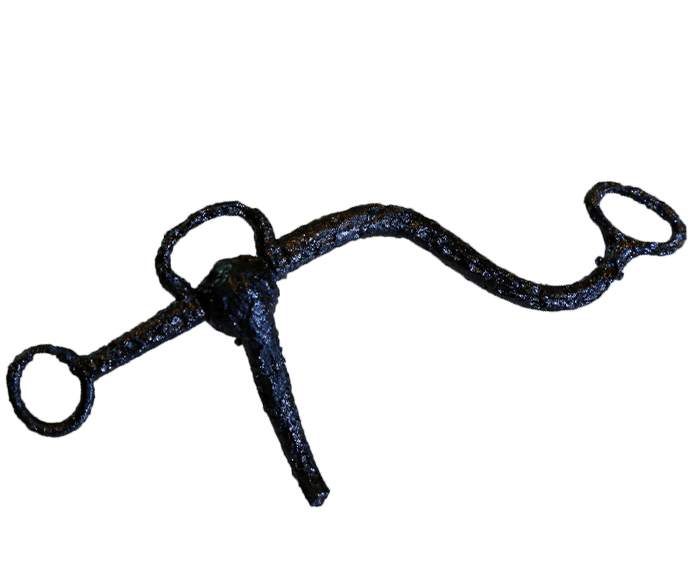

Blacksmith Shop: Several highly skilled craftsmen and artisans lived in bondage at Wilton. The Landing Quarters probably housed coopers, blacksmiths, and carpenters. The homes, fences, and nearby ironworks were likely built by Wilton’s enslaved carpenters: Aaron, Charles, Isaac, and Lewis. The 1815 inventory that listed 94 people as Wilton property also included Blacksmiths Tools, valued at 40 dollars.

The same inventory records 17 horses and mules, whose shoes, bits, and equipment was likely made and repaired nearby. The presence of forge refuse, or clinker, suggests that blacksmith shop stood close by the Landing Quarters. Housing enslaved artisans near their workplace was common and reported both at Wilton and other Randolph properties.

Warwick

Warwick was the only individual emancipated from enslavement at Wilton. The text of his emancipation is the entirety of the known written record documenting his life. From it, we can tease a rough sketch of his life. Warwick was likely a manservant or valet and probably served Peyton Randolph personally for most of his life and throughout the American Revolution. Like Dorcas, Warwick may have had heightened responsibilities and privileges that people enslaved outside of the Wilton house did not. Virginia emancipation law required lifelong financial support for people freed at the age of 45 or older, giving us some clues about Warwick’s age. The Wilton tract was 1 mile downriver from the town of Warwick, established in 1748. Could there have been a connection?

FAMILY MEAL

Here we join a family at the dinner table gathered around a meal of pheasant. Excavations at the Landing revealed a varied diet of Wilton raised livestock, fish from the James River, and despite legal restrictions on firearm ownership by Black men and women, wild-hunted game. Families could come together for moments of near complete privacy in the individual dwellings at the Landing. Traditional practices, faiths, and knowledge continued to be passed down at Wilton. Children were raised and loved. Relationships were forged and they were ended. Bodies were broken and healed. At Wilton, and all across Virginia, life persisted.

Wilton account books suggest that the Randolphs provided the bare minimum in terms of food and clothing to the people they enslaved. Food remains excavated at the Landing Quarters, however, show a widely varied diet supplemented by fishing, hunting, and gardening. The recovery of goose, turkey, pheasant, chicken, opossum, rabbit, squirrel, raccoon, and deer remains suggest an active hunting culture despite Virginia formally banning gun ownership for free or enslaved Black people in 1680.

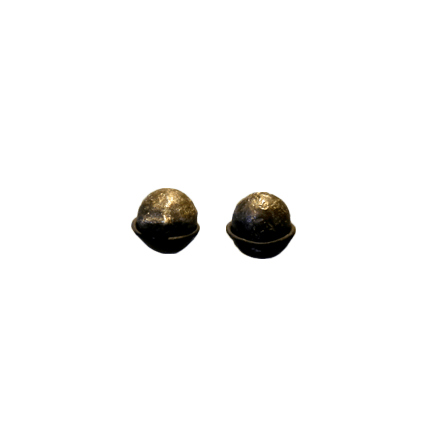

Sub Floor Cellars

Some items, both bought and bartered for, were likely displayed proudly in the home. Other, potentially more personal items, could be stored in a sub-floor pit, or root cellar. Storage pits have been found in enslaved homes throughout Virginia, with some lined with wood or brick. They ranged from just a few square feet to nearly 9 by 6 feet. The cellars in these quarters revealed fragments of colonoware (ceramic forms made from local clay), buttons, beads, folk medicine, and items that may have served as protective charms.

Medicinal items found in Wilton’s subfloor pits include:

• Wild Cherry: treatment for hoarseness, colds, coughs, and indigestion.

• Pigweed/knotweed: used to soothe stomach cancer and diabetes.

• Corn silk: treatment for mumps.

• Mud dauber nests: used for soothing sprains, swellings, and bee or wasp stings.

Beads

Twenty-five glass beads were recovered from the Landing Quarters. Many of the beads found are close matches to 17th-century stock commonly found on Seneca Iroquois and Mohawk sites in present day New York. Nearly identical beads have been found on sites of slavery across the Chesapeake region. It remains unclear if the beads found in Tidewater Virginia originate from a shared source or were simply leftover 17th century trade stock, distributed in the Mid-Atlantic colonies at a later date. This widespread distribution across the east coast creates a compelling picture of colonialism in material culture while suggesting a record of trade and inheritance across the East coast.

“…a very bad fireplace, some utensils for cooking, but in the middle of this poverty some cups and a teapot. ”

Comparisons of trash deposits associated with the Wilton mansion and the Landing Quarters show many similarities. These similarities could represent hand-me-downs or stolen items, or similar purchase patterns. Credit accounts for enslaved people at local merchants were surprisingly common, and while none have been found associated with Wilton, it is highly likely that that Wilton residents also purchased wares from local stores.

Unlike the fashionable full sets of ceramics found in the house, the Landing Quarters show no clear pattern and are unlikely to represent any full sets of plates. Both collections show a large amount of ‘older’ ware types that were slightly out of fashion for their time, and both contained a significant percentage of Chinese porcelain. Future excavations of quarters from other parts of Wilton may be able to determine if the porcelain from the Landing reflected higher socioeconomic status within the plantation hierarchy, or if import ceramics were common throughout the enslaved community.